Some People Can't Be Cured

by Norman Doidge

What, other than our wish that it be otherwise, makes us think that every human vice is treatable by some form of psychotherapy?

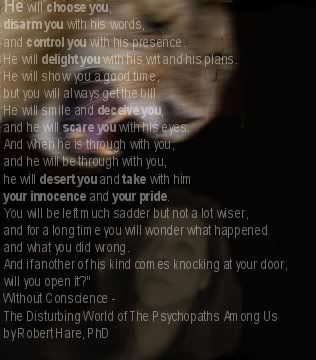

That this wish is not just naive, but, at times, harmful is illustrated by a recent Canadian study on group treatment for 238 sex offenders (rapists, incest offenders) from Warkworth penitentiary in Ontario. These prisoners included some well-documented psychopaths. All were taught to "empathize" with victims, and understand their "offence cycle" as part of treatment. After their release, it was found that those who had scored highest in terms of "good treatment behaviour" and who had the highest "empathy" scores were the more likely to reoffend on release into the community. Hannibal Lecter Charm School teaches good manners, but not morals.

The important study by Seto and Barbaree replicated -- unintentionally -- a 1992 Canadian study that found treated psychopaths reoffend more than psychopaths who are not treated. A larger study, just completed in Britain, shows the same. It may be that all psychopaths learn, in our new ersatz empathy institutes, is how to manipulate better by appearing more caring. But should we be surprised at the duplicity, since such treatments are generally mandated? And are such mandated treatments really psychotherapy?

The important study by Seto and Barbaree replicated -- unintentionally -- a 1992 Canadian study that found treated psychopaths reoffend more than psychopaths who are not treated. A larger study, just completed in Britain, shows the same. It may be that all psychopaths learn, in our new ersatz empathy institutes, is how to manipulate better by appearing more caring. But should we be surprised at the duplicity, since such treatments are generally mandated? And are such mandated treatments really psychotherapy?Just because a self-described "patient" is in a room with a self-described "therapist" doesn't mean psychotherapy is going on. Freud argued psychopaths are untreatable in psychotherapy precisely because having a conscience is a prerequisite for being able to use psychotherapy.

It is the conscience, and the related capacity for concern for others, that drives the serious scrutiny of one's motives, which underlie one's behaviour. Yet psychopaths lack conscience and concern by definition.

But these new psychopath-friendly treatments focus only superficially on motives or matters of good faith by tracking attendance and overt co-operativeness. Mostly they focus on impulse control and teaching new behaviours and mindsets. Past naive, they hope that because a psychopath can appear remorseful, or change his behaviour at any given moment, his overall mindset or deeper intentions will follow suit.

Three cheers for us: We have invented treatments based on theories that are less complex than the impoverished minds of psychopaths.

Psychotherapy doesn't just require a good theory and an astute clinician. It also requires a patient. The word patient comes from Latin, and means "to suffer." A patient, by definition, is bothered by something. Yet most treatments of prisoners originate not from the prisoner's suffering, but are mandated by the justice system. Corrections Canada knows many psychopaths will be released into the community eventually, so it attempts to change them, even though any psychotherapy for adults that has to be mandated is suspect.

The "treatment" reported on in the Canadian study lasted 300 sessions. To their credit, the treaters didn't believe they could work their miracles overnight. Yet, more and more, mandated treatments are short-term: eight to 10 sessions. Most people can't quit smoking in eight to 10 sessions, never mind do a Karla Homolka make-over.

I refer here to the same Karla Homolka who expressed concern for her boyfriend's happiness by helping him kill her sister and a number of other young girls, and who is reported recently to have benefited from a self-esteem course in prison. Such courses, which presume self-esteem can be taught, generally involve telling a person she can raise her esteem in her own eyes by interrupting their self-reproaches or "negative tapes" in her head.

Applying these self-esteem techniques to psychopaths requires an ability to get everything about the psychotherapeutic enterprise backwards.

Psychopaths don't need lessons in clearing their consciences; if anything, it is they who ought to be teaching the rest of mankind how to be remorseless.

But mushy-gushy therapy is not just confined to therapists. It is part of a dangerous denial of the nature of psychopathy and evil that is sweeping through our correctional services. A recent federal task force on security, released on Nov. 2, advised getting rid of guards with guns, unseemly razor-wire fences and intimidating towers around prisons (National Post, Dec. 15). It even advised that inmates should carry the keys to their own cells so they could make "responsible choices." "Restorative justice" based on "a culture of respect" would be practised.

But mushy-gushy therapy is not just confined to therapists. It is part of a dangerous denial of the nature of psychopathy and evil that is sweeping through our correctional services. A recent federal task force on security, released on Nov. 2, advised getting rid of guards with guns, unseemly razor-wire fences and intimidating towers around prisons (National Post, Dec. 15). It even advised that inmates should carry the keys to their own cells so they could make "responsible choices." "Restorative justice" based on "a culture of respect" would be practised.So here is a respectful way of framing things. Psychopaths constitute 1% of the population, but are so talented they conduct 50% of all crimes. Since it might be hurtful to say they are incurable, let's just say they are beyond therapy.

That much said, surprising as it sounds, not all sex offenders are psychopaths; some, who have been involved in incest, apparently have low rates of reoffending. Some may benefit, at times, from long-term intensive interventions and monitoring. But there is no empirical evidence that sex offenders who are psychopaths benefit from treatment.

The federal report is a miscarriage of justice, and a miscarriage of mercy. It is based on a distortion of religious notions of forgiveness, political notions of equality, a scientific zeal and an unwillingness to make basic distinctions.

In ancient times, Aristotle made those distinctions, and developed a hierarchy of virtue and vice. At the top of the ladder is the virtuous person, who only aims toward good things; he is not "conflicted," as we would say, because there is no war between virtue and vice in his soul. Next, comes the continent person, who behaves well, but is always a bit tense because he is struggling, albeit successfully, to control his vices. Then comes the incontinent person, who knows what is right, but who frequently slips up, failing in his struggle.

At the bottom of the hierarchy is the brute -- our psychopath. Like the virtuous person, he, too, is not at war with himself, is not "conflicted." Unlike the virtuous person, it is vice, and not virtue, that rules. Aristotle thought there was something different in the physical makeup of such people. Indeed, recent brain scan evidence shows some psychopaths do have altered brain structure and functioning.

Our mistake (based on mindless extrapolations of our notion of political equality) is to collapse all these distinctions into the continent or incontinent categories. Indeed, we are as irked by notions of the virtuous as we are of the vicious.

Comments